“… If you think there is a purpose to life, then I at least don’t know how to find one that doesn’t connect to something that transcends our little mortality,” he tell me. “I think a lot of people at some level- again, either explicitly or implicitly- will do science or art or something because of the sense that you do get to transcend something. You touch something eternal...” (emphasis mine)

Nima Arkani-Hamed, speaking with Katie Mack in her book, The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking).

Even if you can agree that science and art can complement each other, they are still often portrayed as paths diverging in a wood. I know, for me, it was positioned that way in my earlier years - that there was, and remains, a hierarchy of one being a noble pursuit, and the other, a mere dalliance that can only be enjoyed when real work is done. (Ah, that sweet Protestant ethos.)

And it occurred to me that even though I consider the two disciplines to be companions along the same continuum of beauty, I have perhaps positioned one as lesser than the other. That is, in talking a lot about art as a means to share science, that I have perhaps portrayed the creative discipline as something in service of another.

This isn’t spurred on by any particular comment I’ve received, nor any herbal substances inhaled or digested. It’s merely the thread I’ve pulled following the tangents my thoughts will sometimes take. I was exploring the idea of reaching out to and interviewing #SciArt initiatives and organizations to learn more about their craft (so that I could then share it here). In doing so, I drafted possible questions, starting with two:

Why is art important to science?

Why is science important to art?

And it was here, on this second question - merely the inverse of the first - that gave me pause, because I realized that (my) assumption up to this point assumed a direction of the relatonship. A hierarchy, where art is used to the benefit of science. (I would hazard to say in others, too, have held similar biases, if we look at how we talk about science and art. I mean, it’s #SciArt, not #ArtSci.)

Of course, art has played an important role in making science more democratic and thus more accessible to a wider audience. To riff on Sagan, we need more candles in the demon-haunted world, and if we need to draw or paint or sing about the candles to light our way, so be it. But science in service of art - to manipulate the variables to create matter (and play with the very meaning of the first rule of science fight club, i.e., the law of conversation of mass)?

Perhaps this all sounds daft - the musings of someone clearly in need of the vacation coming in a few mere days: “Bryn, of course science is involved in the creation of art; how else are art materials created, if not through the outputs of chemistry, physics, engineering?”

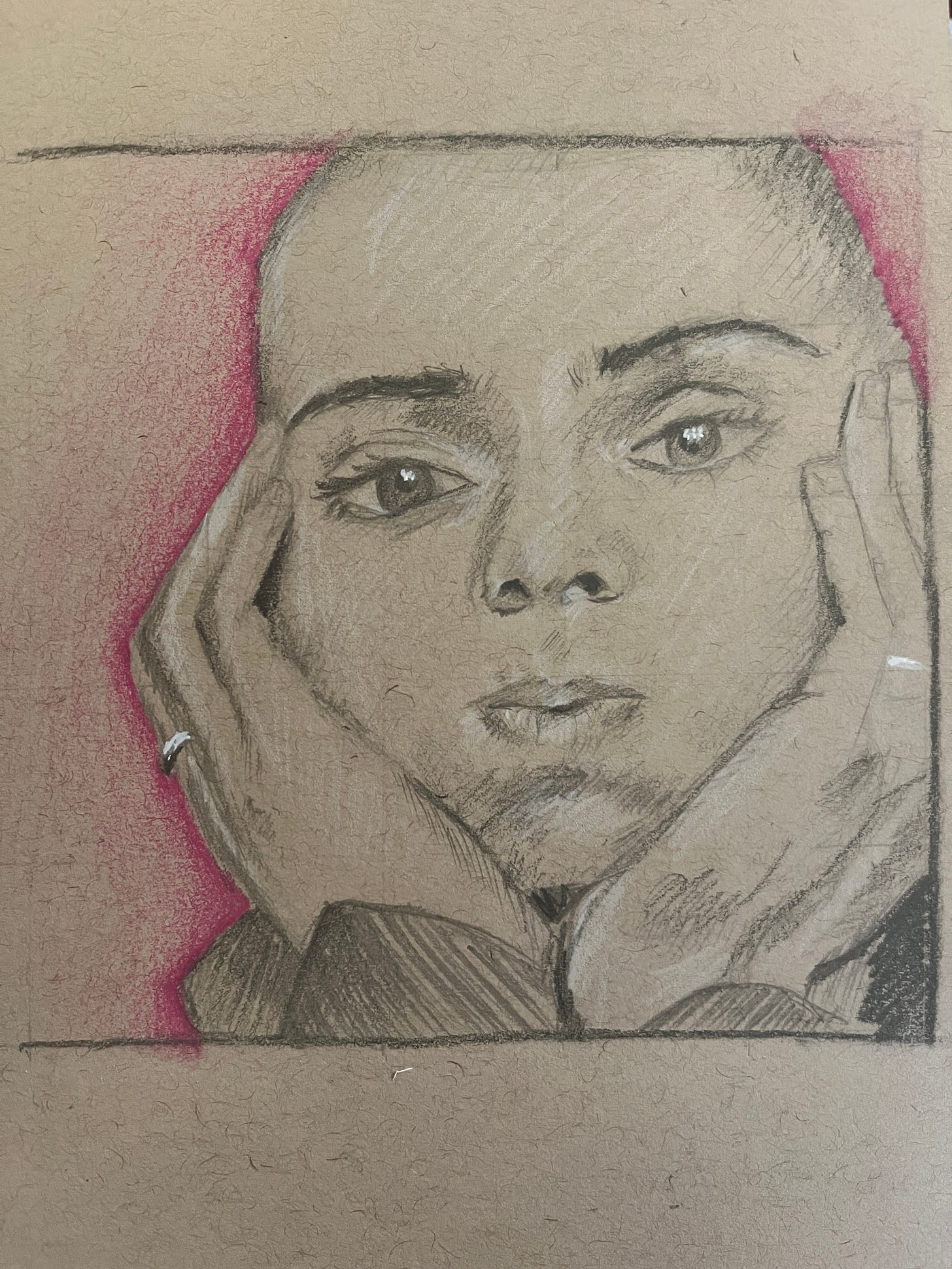

I’ll beg forgiveness, for I guess you can take the girl out of the debate club, but not the debate club out of the girl: What I was thinking was more purposeful knowledge; being more mindful of the ingredients from a scientific lens, so that we can push them to the limits to create pure magic. Paying more attention to tooth of paper, pigment and binder, air quality, humidity, so that when pen hits paper, the only barrier that remains is your headspace.

Then again - I can hear my debate club colleagues crowing across the wobbly desk serving as podium - if you need art to tell the scientific story, maybe art holds the power there? And needing scientific knowledge to maximize artistic output gives the edge to science in that regard?

What do you think?

Maybe it’s all equal. Maybe I really need that vacation.

(Maybe it’s both.)

When I was a music major at York University, each of the disciplines had a mandatory science course related to that art. For music and film it was the physics of light and sound, for dance and visual art it was anatomy. I, of course, wanted to take anatomy because it was one of my interests, but because I was a music major I had to take the physics class.

I learned so much about acoustics in that class that it influenced my music and composition practice in an intense way. This was literally science in service to the arts. And I wish there had been more of that in elementary and high school.

I think we’re inherently creative beings, and traditional academic institutions too often deny and tear out that creativity, trying to sever it off from us so we believe we aren’t good at art or that only some people are creative or that science as you said is the more noble pursuit.

I think we need to return to a type of learning that weaves it all back together. You certainly are not daft 😊

I, too, have spent most of my life imagining art as something so separate from me and the superior factual knowledge I have . But that’s not true, I don think. Not at all.