Complementary Colours (#105)

Connecting to science in creative ways. Or, what I recently shared with health students and professionals at a recent end-of-year research symposium.

The following essay is actually a talk I gave on Thursday, April 11, 2024, as a keynote for the University of New Brunswick’s Integrated Health Initiative Research Symposium. I thought it would be good to share with you, as it talks about communicating science with creativity. Aside from 3 photo credits, all the words including captions, and the photos, are from the speech. Let me know what you think about using art to share science in the comments.

I was at a pretty young age when I first became captivated by the world of science.

Although, it was an inevitable outcome.

It was inevitable when, at a parent-teacher night when I was in the second grade, my folks came home with a colourful new book from the Scholastic Book Fair.

There were certainly many books out there that could have told me how to wrap plastic film around a series of coat hangers to create a miniature greenhouse that, compared to the unhoused green seedlings, would allow a sub-sample of tiny beans and peas to soar into the sky. Or at least until they reached the ceiling of the plastic wrap.

But this book was different.

It took me by the hand and asked one to take action. It had delightful illustrations and easy-to-read steps woven together that easily encouraged children to raid pantries and craft closets for materials. It connected with young budding scientists who previously had no knowledge of this world of experimentation and replication and recording of results.

To me, this book was a key magic moment for me, like it no doubt was for many other kids in elementary schools across the country.

Perhaps you, too, can trace your own path back to a magic moment or two.

And for me, it was the beginning step of a path that would take me to immersive science camps and interactive museums. It would lead me to search for a laboratory to eventually call my home - which I did right here at this school, for both an undergraduate and a graduate degree.

Of course, like many others on this path, part of being able to make this journey was to become fluent in a new language. This language, we perfected over repetitions of tightly formatted sentences in blue hardcover notebooks. We learned specific reference styles and jargon and how to black out the “noise”, until all that remains for future researchers’ inspection is that which tells us how it was done and why.

We become used to thinking and writing at a long distance, detaching ourselves from our own unique viewpoints on the world - our own positionality - as if we were observing a scene in another person’s life entirely.

And that’s indeed a critical feature baked into the production and replication of science - recording the facts in discipline-specific lingo and in enough detail so that anyone else can pick up the article or report, and understand precisely how the study was run. More importantly, it lets others assess whether the choices and the conclusions made with the available data are accurate and appropriate. To judge science without bias, you need an unbiased accounting of the work completed.

First, what is the problem with sharing science in the language that we have all been trained in? Nothing. The research we do has to be clear so that it can withstand scrutiny and peer review; so that it provides a foundation for other scientists to judge its merits and then build on it. Even the person I would call a father of popular science communication, Dr. Carl Sagan, professor of astronomy at Cornell University, would speak to his fellow scientists in the dispassionate prose of the academy. That common language is necessary. I did it. I still do it. I will still do it in the future, because the language has a place and purpose.

There’s nothing wrong, except we’ve extended the same language, tone, vocabulary and sentence construction to any communication we try to make about research.

Sharing science in this way is to assume that we all learn by brute force; that is, if we force-feed people the evidence from studies for long enough, they will simply be convinced that what is presented is important and worth considering. And it limits us to only speaking about science to a small group of people.

Further, we know that there are challenges even getting the information into others’ hands through our traditional channels. If you’re familiar with the “valley of death” concept of knowledge translation from CIHR, in which there are gaps in the transfer of knowledge from lab to bedside, or bedside to the wider world of application. Or if you’re familiar with the oft-cited statistic that it takes, on average, 17 years to get the information we generate in science into others’ hands for consumption.

Because of that, it is arguably no longer sufficient for science to have just this one language, because that one language limits our ability to connect with others. This is especially underscored by the recent global pandemic. We need to connect with others more than ever before.

So, I think it’s time that we become bilingual and embrace a new language of creative (and thus more accessible) science communication.

Yes, I’m talking about art.

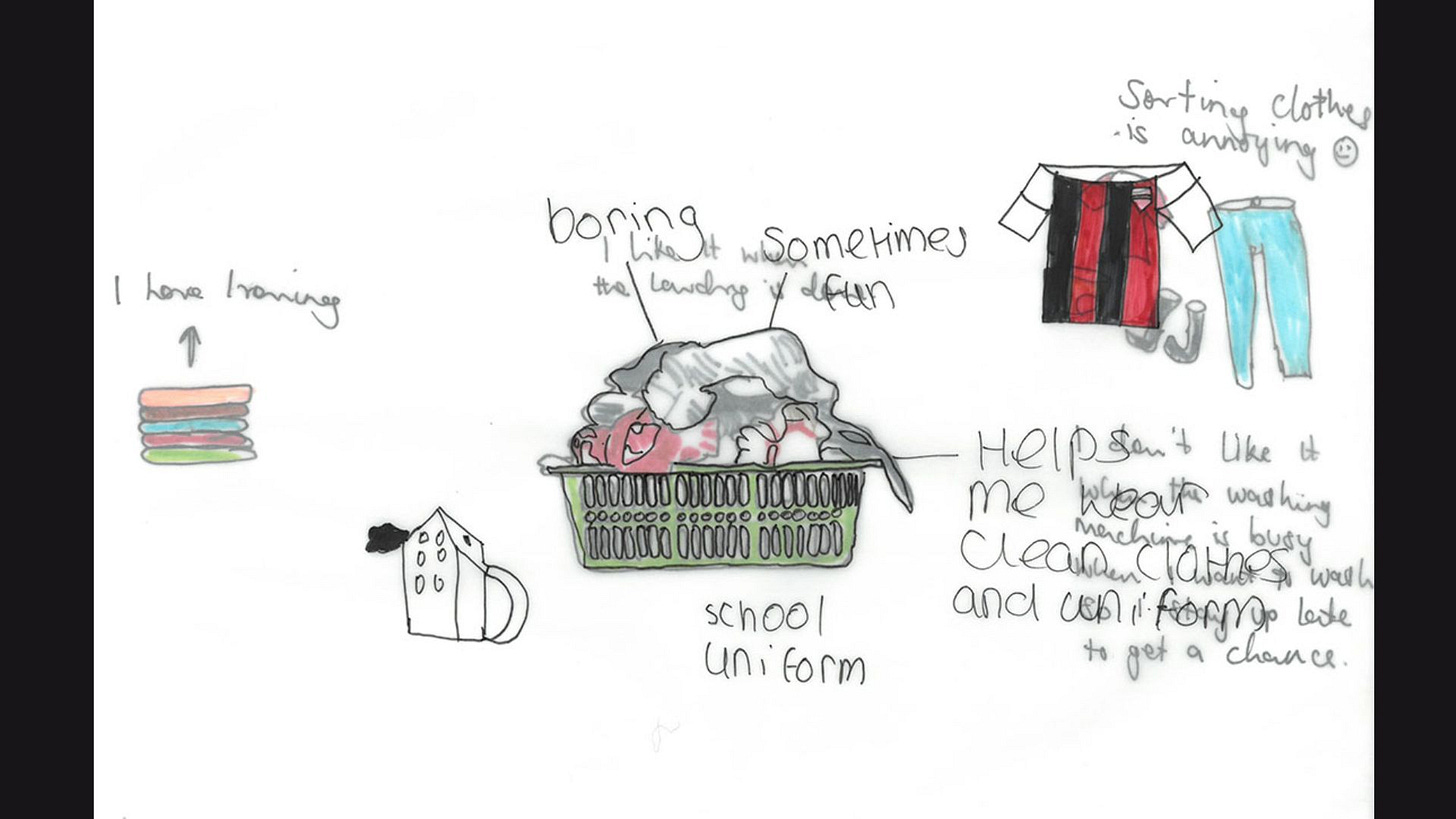

In some spaces, art has a partnership already with the production of science, through qualitative research that empowers a participant to explain or demonstrate their thoughts, emotions, and experiences in ways that the spoken or written word cannot access. It can help the participants initially put to words what may be otherwise difficult to express, and is a great tool of empowerment when working with underserved or marginalized populations.

But I’m talking not about the creation of data but about the communication of data - such as in this early and very famous example shown through Darwin’s drawings of the Galapagos finches, wherein the illustrations of beak shape and size helped to facilitate an understanding of the profound impact of natural selection.

I first became interested in learning the language of art in science - #SciArt as it is often dubbed online - as someone whose role involved helping others share their science with larger and more diverse audiences than we have traditionally reached with posters and articles.

Initially, it spoke to me because I personally enjoy making art and taking in others’ art; it felt like a marriage of previously separate parts of me. I would take breaks from studying as a student to learn oil painting in a local school basement, or to walk around my neighbourhood learning how to take photographs.

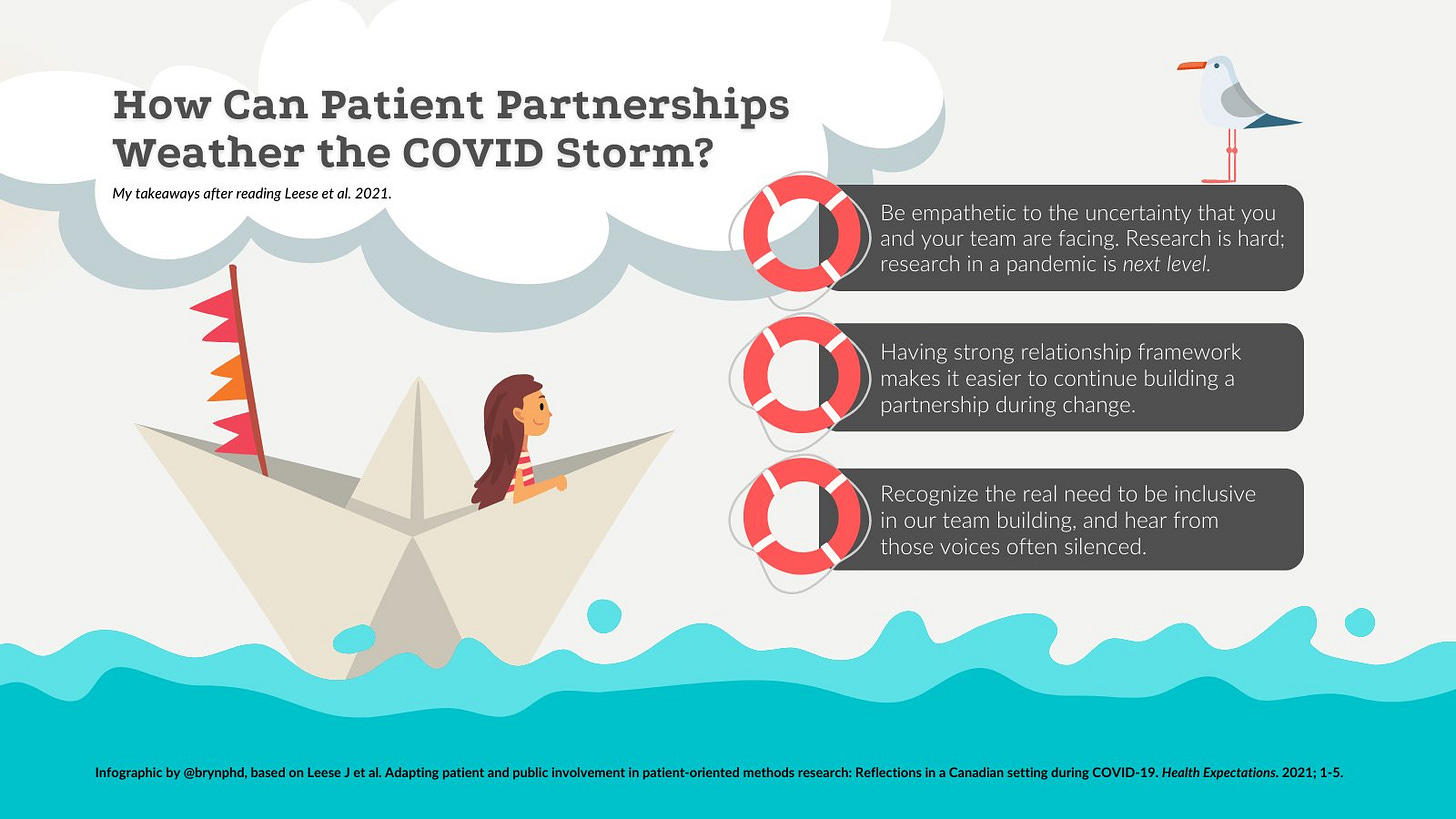

But I read more about the challenges and realized art was actually complementary to science. In both disciplines, the creator - the artist or the scientist - want to make sense of the world in new ways, and they want to present and communicate the world to others. So I started doing that with articles or more informal concepts that resonated with me.

In another one, I was struck by Rachel Martens’ comparison of patient engagement work to making raisin bread; that there are common ingredients across all the recipes out there for raisin bread, but that there are differences, too, and not everyone is going to like that particular recipe. And how that’s okay because those recipes reflect local and personal importance.

Let me share other examples that have fascinated me over time, as I continue to learn about this world.

Take the work of Dr. Mark Gilbert, who did a residency here in Saint John and collaborated with pediatric neurologist Dr. Wendy Stewart to capture experiences of youth living with epilepsy. (They did this work before I got fully stuck into #SciArt; I wonder now if it perhaps was fertilizer for my own growth.)

In this example, a professor and artist created a series of beautiful dresses inspired by what was seen under the lens of a microscope.

Similarly, what about the conversations on seeing embroidered zebrafish cells?

Or what about using seemingly infinite vibrant lines to communicate the experience of living with the seemingly never-ending spiral of vertigo?

I could spend days sharing images that capture my imagination. Across any of these examples, and the many more that continue to be developed out there, we have two different views of a topic or message. One could argue that adding art to sharing your science makes it more memorable because it adds a layer of encoding. The scientific message communicated is shared through language but also through visual and emotional cues. The art provokes new connections and springboards for further ideas.

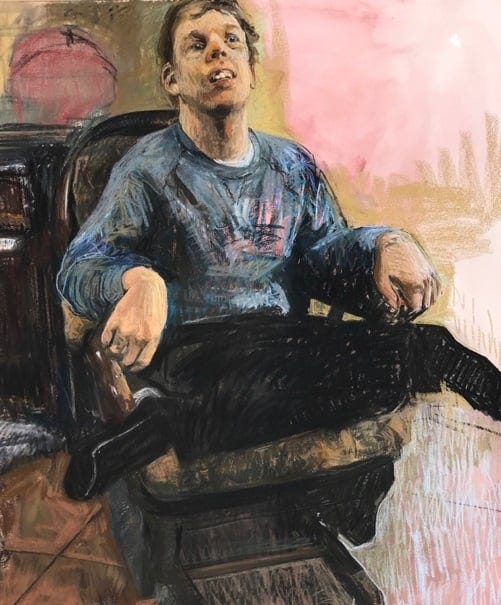

I wonder, too, if the art makes scientific messages memorable because creative expression has this ability to infuse humanity into experience.

People remember how something makes them feel, whether it makes them smile or feel empathy or amused or fun or sad. And when we introduce this layer of humanity into the communication, we provide a means of connection that is more approachable, accessible, and familiar. We build a common place of entry into the world you’re exploring that allows people to walk together through that door and ask questions together. The person doesn’t need to know about the finer points of fitting data to models and genetic expression.

This is especially salient as health research in general shifts to be more patient- and public-oriented.

People cannot connect to what we do. But they can connect if they are enabled to find, use, and build on the work.

There can ideally be a dialogue, where the researcher receives questions, but also can ask questions back to the person for further clarification and expansion. Here’s one example of the layperson-researcher feedback loop produced by a SciArt collaboration.

Our current system has supported the creation of a veil of secrecy and superiority, we’ve created this othering. This “othering” creates disinterest at best, and mistrust and fear at worst. But we are all the system, and each of us has the capacity to inspire change. We should want people to ask questions about our work - one could argue that it’s even in our duty to ensure that people who can use the research have access to it - but to invite the questions, we need to set a better and more welcoming table for our neighbours to know what we’re working on and why those questions are important.

To have people connect to our words on a personal, emotional level, we need them to first understand it. And to understand it they need to access it.

We can use art to provide a path around paywalls or limitations imposed by general or scientific literacy. Quite simply, it’s about democratizing science by giving people a secret decoder ring to your work.

It served to highlight to me that, if people understood more of the scientific process and the questions we ask, big and small, we would get more people interested. More people would understand how science works and what it should look like. They will be more attuned to seeing and hearing about the work and the processes and the questions that go into science. If more people knew about it, you’d have more awareness about the work. More people in your corner, in the corner of science, that understand.

So creativity in knowledge translation is important because it democratizes science and enables more people impacted by your work to find it, use it, and build on it.

On the simplest level, though, there’s a practical purpose to finding creative means of expression for your science.

Wouldn’t you want your work translated into another language to connect with more people - more people potentially who could use your work? Sometimes, I think we are hung up and focused on hearing about those huge discoveries. But we forget the puzzle pieces that need to happen to get to that larger work. And we also think that we cannot make a big deal of those smaller pieces because they’re not big enough.

Why? Your question may be small, but it’s valuable and deserves a few more people to know about it.

And, to be honest, it’s fun. It matters because it makes science richer for us as researchers and scientists. Despite best stereotypes, we are not single-celled organisms that can only experiment, publish, and repeat. Why can’t we have fun and share that joy with others?

So, to begin wrapping up, creative knowledge translation for science works because:

It makes science memorable.

It stays memorable because it infuses humanity into science.

And because it infuses this pathway, it provides a means of connection that is more approachable, accessible, and familiar.

I hope that it’s clear now that I’m not advocating for the loss of one language but that you consider becoming bilingual and learning a new one (or finding a suitably fluent translator to partner with you). People will say, “Oh, I’m not artistic.” First of all, you might be more equipped than you think. For example, consider the “Sticky Note Challenge” (also known as #PostItNotePhD over on Dante’s Birdsite) - both a thoughtful exercise for the scientist and a creative knowledge translation vehicle to share findings with a larger audience. It’s a visual version of the elevator pitch, but I think it’s even better. It asks the researcher to identify and distill the key takeaways, and it presents those takeaways in a visual piece that lasts longer than the traditional 30 seconds of the elevator pitch - allowing more time to process.

But if you haven’t found the specific artistic dialect that works with your talents, you can partner with someone who has the language you want to use.

Learning a language of creative knowledge translation is important, because:

It enables more people to find and use your work.

It democratizes science for a wider audience.

It makes science richer for us as researchers and scientists.

What especially excites me about the potential for creative knowledge translation is that these connections may not just be between concepts, as the art leads you down a new line of thinking, but between people. The art brings us together on a common ground free of scientific jargon to share our individual thoughts, and maybe even seed the beginnings of a new relationship.

Even reaching one more person is a big impact.

After all, if you got one kid to hear about it, it might change or solidify their interests in what they do.

And wouldn’t it be cool to be someone who brings a little magic to the next generation of scientists and researchers?

Ha, ha… wouldn’t that me great! I can do a Newfie jig!

Bryn! This is amazing. Wish I could have seen/heard you deliver it in person, but thank you so much for sharing it here. You articulate so much that’s important, and in such an accessible way. Thank you!