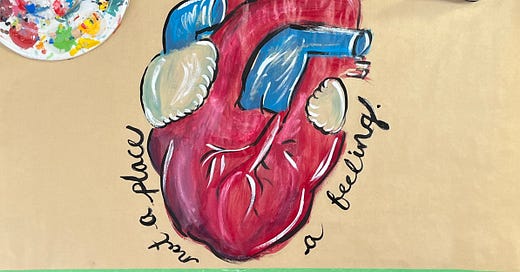

#46: Not a Place, But a Feeling.

The challenge is in finding the medium, or media, that best fits the narrative you want to share.

“If you've got a story you want to get out there and you've got a really good image

…it will fly a lot farther than just words.”1

Scrolling through the latest entries on the #SciArt hashtag and related Twitter community, I’ve often wondered about the place of the scientific illustration.

Specifically, in a world where we can - and do - document with digital cameras every moment in startlingly accurate detail, how has the illustration persisted as a medium of science communication?

Nearly twenty, and looking for respite from the anxiety that nagged at me, I spent a term of Tuesday nights in the depths of an elementary school basement. Rubbing elbows with retirees, we sipped on acrid caffeine from Styrofoam cups, and nibbled on tiny sugary biscuits. The insistant fumes of paint thinner and instant coffee draped our hunched-over forms, scraping pigment and resin onto canvas boards. Learning the building blocks of oil painting.

Over that winter and spring, I tried to recreate a moody seascape I had torn from one of the magazines in a back corner of the classroom. I hadn’t found my inner Bob Ross, though. I was an unforgiving perfectionist at that age (still recovering, if I’m being honest), and the end result never captured the depth and dramatic light of the stormy purple cliffs and ocean.

A few years later, I picked up a camera, and something clicked.2 Crouching behind the viewfinder, I could suddenly convey more honesty and truth with light painting a sensor through a lens, than with brush strokes on canvas, or pencil on paper. And, I had the benefit of easy practice and immediate feedback. The first image is rubbish? Try again, and take ten more. You didn’t have all the preparatory steps that setting up paintings can take.

Of course, the difference was that all that practice was teaching me how to actually look at the world. To see composition, colour, and shape. To look at the way the light bends and curves, and make adjustments.

Perhaps most importantly, it was learning to let go - to not make the art “precious”. Once you’ve decided you’re creating a masterpiece, you work stiffly, already in editorial mode and not creating mode.

Continuing my own art journey, I’ve recently come back full circle to the role of illustration versus the photograph. Given the ease of creating an image with a camera, why does science lean on illustration for its’ textbooks, pamphlets and videos?

Some argue that illustrations are preferred in science for their abilty to represent the truth more accurately; for example, precise details may not stand out or have enough contrast in a photograph3 due to a camera's hardware limits. Illustrations can have greater longevity4, too, not constrained by stock photography models' dated outfits or surrounding decor. These seem like weak arguments to me, though, especially as cameras, lenses, sensors, and editing software continue to improve.

What I think it comes back to is a lesson I learned a few summers ago, during a drop-in figure drawing class at the Smithsonian.5 I was in DC for a week playing tourist while Ben attended computer camp6, and how cool would it be to go to the Smithsonian and take an art class?!

The instructor (yellow sweater standing up front) gave wonderful nuggets to help us be more loose in our sketches, including, “You’re not making a carbon copy. You need to communicate the essence of our model.”

What’s the essence of a science story? And, depending on the medium’s ability to tell the story7 we need it to tell, is the photograph or illustration better in this case?

Although comparable, a photo and a painting should not be compared when it comes to art. Because each one of us wants a different story. Some find that in a photo and some in a painting. None is better than the other, because they both are talking to us, by evoking memories and by telling us stories.8

In short, the illustration persists because it tells the story we need it to tell in that textbook, or that slidedeck.

A feeling, not a place.

Madhusoodanan, J. Science illustration: Picture perfect. Nature 534, 285–287 (2016).

Pun absolutely intended.

Perelli K. (6 Mar 2019.) Why We Need Scientific Illustrations.

Losers G. (5 Oct 2016). 10 Reasons to Use Illustrations Instead of Stock Photography in Learning.

Yes, I know. Lah-dee-dah.

More specifically, SANS, which teaches you how to hack and defend against hackers. He sat in a hotel conference room for six 12 hour days, I walked around DC, scoured used vinyl shops and ate cupcakes. We both won.

And if you’re Canadian and of a certain age, you’ll remember good ol’ Marshall from that Heritage Minute.

No author. (27 Feb 2022). Which is better: A photo or a painting?

Oh wow, Bryn, great post!

It's amazing how differently representational photography and drawn art relating to objects and life forms can be, isn't it? I find that botanical drawings of flora, those beautiful bird books with their gorgeous painted pictures of our avian friends, and anatomical drawings like your stunningly-rendered heart are easier to digest than photographs of the same. For these more generic things, drawn art is great.

But drawn art doesn't cater for the very specific, 'right here, right now' need for illustrating, say, a precise location at a given moment, or a news story, or a 'this is what I'm looking at - can you see what I mean?' For that we need photographs.

I've really enjoyed reading this post, and I'm going to be thinking about it for a while!

Oh, I love your heart drawing! It's beautiful.