#58: Layers

On fighting yourself, and seeing sunflowers.

Composed of innate (i.e., the white blood cells and organs that serve as our original defenses) and adaptive (i.e., the proteins that we create “aftermarket” through exposure to disease and vaccination) parts1, our immune systems are ready to protect us against the microscopic challenges of life on Earth.

And for the most part, it works and we’re unaware of it. Well, until we’re fighting a cold or flu, and then we are very aware of the system’s hard work. There’s an increase in body temperature to make us more inhospitable to the intruders, but which also leads us to sweat and shiver in misery. There’s gunk that traps the bad guys and all the dead immune cell soldiers, but which needs to be sneezed or coughed out seemingly without pause. But despite this nuisance, it’s only a short time before the symptoms (typically) ease and the immune system stands back down.

Sometimes, though, it doesn’t stand back down; or, it prepares for battle without any opposing forces on the horizon at all, but decides on its own that it’s spoiling for a fight.

“You can’t muscle your way through the enervation and malaise of autoimmunity—if you could, I would have. The real coming to terms with autoimmune disease is recognizing that you are sick, that the sickness will come and go, and that it is often not the kind of sick you can conquer.” - Meghan O’Rourke2

Why our bodies sometimes turn on themselves is a complicated question - one I’ve been thinking about it for about 31 years. Having just run across a playground, all I had to do to get back to the cottage at Fundy National Park was cross some parking spaces and a road without incident. But I am Bryn, and this Tuesday’s child has zero grace. I tripped, scraping my right shin. It stung and oozed, but the irregular oval was quickly patched up and I went about my grade 5 business.

It never quite healed, though.

Concern for circulatory issues from diabetes (something I had only heard about at the time from The Babysitters Club) was tested and ruled out. By this point, my scalp was starting to itch like crazy, and there were bumps under my nose and in my ear. My family doctor referred me to a dermatologist, who quickly figured it out.

Seemingly unconnected, the symptoms were all the same thing - a genetic predisposition to attack my own body, switched on by a tumble over a concrete parking curb.

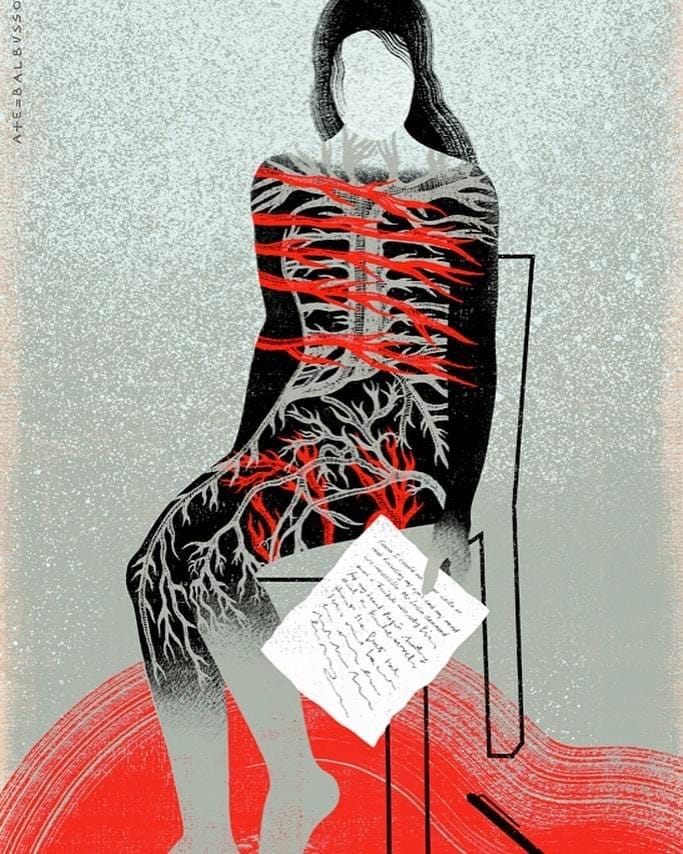

You might point out, and rightly so, that I always find the interplay of the lived experience and art fascinating. Autoimmune diseases have a particular quality, though. They can be well hidden from plain view, and treatments to dampen the immune system may require the person to lay low. While immunosuppressants can improve symptoms and functioning, it can come at the cost of limited socialization, lest the person come into contact with a virus, bacteria, or fungus that a more intact immune system would easily ward off.3 In other words, over a myriad of physical and mental aches and pains can be a loneliness, sometimes so intense it borders on violent. I imagine there are rich emotional experiences living with autoimmunity, and art can provide enlightenment and education into the nuances that are all-too-easily reduced to focus notes in charts.

And indeed, that’s what I find - deep thoughts and complex techniques to share them. For example, in a previous post, I shared the exquisite work by Lia Pas, who embroiders her myriad of myalgic encephalitis symptoms. In The Body Lives Its Undoing, the experience is rendered a little less lonely by virtue of the collaboration used to create it: a poet, visual artists, people with lived experience of autoimmune disease, caregivers, and researchers, working together to share “breathtakingly honest poems complemented by curated artwork”. (You bet, I ordered a copy - stay tuned!) Similarly, by creating an online Autoimmune Expressions gallery, the Autoimmune Association not only showcases works done by artists and poets living with various autoimmune diseases, it creates an opportunity for further connection.

“Psoriasis develops when there is a malfunctioning of the immune system which causes inflammation. White blood cells (T cells) in the immune system are triggered and this causes inflammation to occur, which then causes skin cells to rise to the surface and shed at 10 times the normal rate.” - Canadian Psoriasis Network4

I’ve seen the dermatologist, on and off, since the first scar that never healed. I’m very lucky that I don’t have to see him very often. Since the initial onset at age 11, I’ve probably had two to three flares of varying lengths of time. Plus, my family doctor has increasingly felt comfortable enough to run a new prescription or raid his sample cupboard without having me wait months for a specialist visit. I’m fortunate; others in my family, with larger swaths of affected skin and the associated rheumatoid arthritis I have so far evaded, have graduated to UV therapy and injections that suppress their immune system activity greatly.

Currently, I have a few small spots re-emerging - always that same right shin- that I slap on a thick salve of coal tar. I’ve used steroid creams in the past, and they’re great at reducing inflammation and suppressing immune cell activity at a local level, but they’re only for a short period of time. Smelling like, well, pavement, the coal tar slows down the rapid turnover of skin cells, and has the added benefit of long-term use.

(How someone came to the idea of smearing it on skin, though, is a mystery. Maybe an equally graceful person with psoriasis fell on a freshly-paved road over 100 years ago?)

Originally, when I was looking at examples of autoimmune art, and became inspired to create my own, I had a fuzzy concept in mind: “nice” skin juxtaposed with a collage of junk mail to depict the problem area. When Ben, my husband, saw the underlying sketch and the flyers, and asked about the concept, he wondered aloud whether acceptance was perhaps kinder than considering a part of me as “junk”.5

I paused for a few beats, and set aside the Canadian Tire advertisements for a local gardening catalogue.

Did you know that sunflowers are a symbol of self-acceptance?

Me neither, but now I like thinking of the spots that way.

Johns Hopkins University. The immune system.

O’Rourke M. (19 August 2013). What’s wrong with me? The New Yorker.

During a pandemic, the last thing you want to do is turn the dial down. You want those white cells to fight for you.

Canadian Psoriasis Network. How does psoriasis work?

He has a great eye, despite being an engineer.

I liked your "Layers" collage. Also Ben's comment. 🙂

A beautiful post, and such beautiful art, Bryn. I love how you've represented yourself here, and I'm tempted to try some autoimmunity art of my own. Thank you for the inspiration!

I've never come across The Babysitters Club, but I remember getting very upset with Julia Roberts portraying Shelby, the character with diabetes, in Steel Magnolias. 'I'm nothing LIKE that when I'm hypo - she's massively overacting!' I told the person watching it with me. 'You're right: you're NOTHING like that', he said. 'You're WORSE!'

Charming. 🤣