Strength From The Earth (#77)

On the eve of the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, some reflections.

The Anishinaabe term for medicine – Mshki ki, for example – derives from the words Mshki, meaning strength, and ki, which comes from the word Aki, meaning earth. It translates, therefore, as “strength from the earth,” and demonstrates the fundamental relationship in traditional medicine between the individual and the natural environment.

(Heritage Canada, 2016)

When I walk outside in the woods, I’m surrounded by silence and cedar.

Yet despite this blank canvas, there are times when I lose focus on each step. Or, when I become too focused - on tracking a potential new lifer (that more often than not turns out to be another song sparrow), on the conversation flowing between Ben and I. We disconnect from nature despite being immersed in her home, the environment lifting around us like the fog that is slowly lifting off of the nearby Hammond River.

In between thoughts shared, or with a sudden sharp snap of a branch, though, I refocus and truly drink in the beauty of our the surroundings: the impossibly tall maple and birch, interspersed with thick, textured cedar. The steel-blue crushed rock trail helps illuminate the sap green cedar leaves fallen over it - likely, victims of the recent tropical storm that thankfully did little in way of damage to homes and people, but shook the foliage loose. The connection with the earth helps realign the humours: blood pressures and blood sugars, muscle tensions and tender hearts.

Medicine takes many forms, and for a Western-cultivated mind, it challenges to incorporate other definitions of healing. Yes, while there are are many medical marvels in Western medicine, where it can fall short is its compartmentalization of mind, body, and spirit. That is, when it becomes too entrenched in a singular way of knowing; when it focuses only on the physical body ignores the very real impact our minds and our spiritual lives (if we have them).

There is no single Indigenous or Western way of knowing. It is easy to fall into the traps of ‘homogenizing’ and ‘othering’ by reducing vast and varied traditions to simplistic and general terms. Western researchers often treat knowledge as a thing, rather than as also involving actions, experiences, and relationships. Western thinking tends to view the land as an object of study rather than as a relation.1

Last fall, I was grateful for the host of steroid creams that calmed my inflamed skin that took the appearance of the lichen-laced trees that currently surround my hike.

But it didn’t completely extinguish the fire that was sparked by my mind, overflowing with errant anxiety and emotion pushing out of this container wherever it could.

I needed more healing.

I needed other medicine.2

I needed to understand more how I am interconnected with the world around me, both human and other. I needed to slow down and reconsider points of view.

In Canada, this Saturday (September 30 each year) is the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. It is a very recent national day of observance established federally and provincially to remember and honour “the children who never returned home and Survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities.” It also asks us to consider how historical and current policies have had - and continue to have - impact on the lives of Indigenous peoples in the country.

To that end: if you’re interested in learning more about a piece of Canadian history that was most certainly not taught in schools when I was a kid, the University of Alberta has an excellent course called Indigenous Canada.

Consider it a prescription to consider other ways of knowing.

Links to Artwork

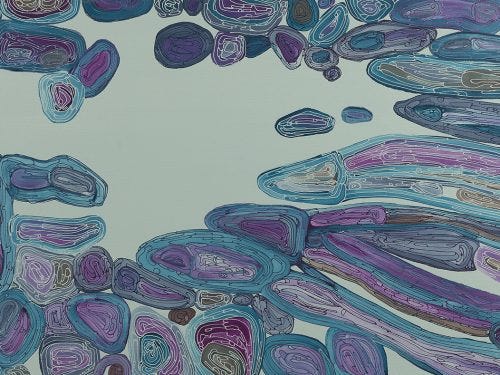

Gallery 1 images come from Stories and Structures: Aboriginal Art Meets the Microscopic World, where scientists teamed up with Aboriginal artists in Australia to compare and contrast representations of molecules.

Gallery 2 is images taken from the Instagram account LottieBeth Beads; I found Dr. Jamaica Cass’ work originally via this story: The healing power of art: Indigenous artists bring to life Indigenous healthcare education resource

Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women. What are Indigenous and Western Ways of Knowing?

In an era of growing anti-science rhetoric, I feel the need to offer a disclaimer here. There is a difference between acknowledging the need for multiple perspectives in tackling a problem (multiple “ways of knowing”), and espousing unhinged false belief (i.e., just because you want to believe that vaccines are a mechanism of mind control by the elite doesn’t make it true.) I continue to consider the differences, but it inherently makes sense to me that, with the former, we’re discussing topics of import to improving science (e.g., how we see and shape our approaches to study) versus baseless copy pasta.

Beautiful reflections and shared artwork, Bryn 😊 especially as the earth is changing so much right now !