Uncomfortably Numb (#79)

We gonna rock down to Electric Avenue, exploring that fearful mental illness treatment in the second Spooky Science 2023 post.

I’m surprised that I’m not hearing more noise down this corridor.

Indeed, I expected more.

I mean, sure, there is the white noise hum of people moving in and out of rooms with efficiency and purpose and trolleys laden with devices, charts and bottles. But instead, there is a noticeable absence of other noises; for example, the consistent mechanics and distinct patterned beeping of an IV pump, doling out droplets of medicine through salt water, is missing.

There is a crinkle.

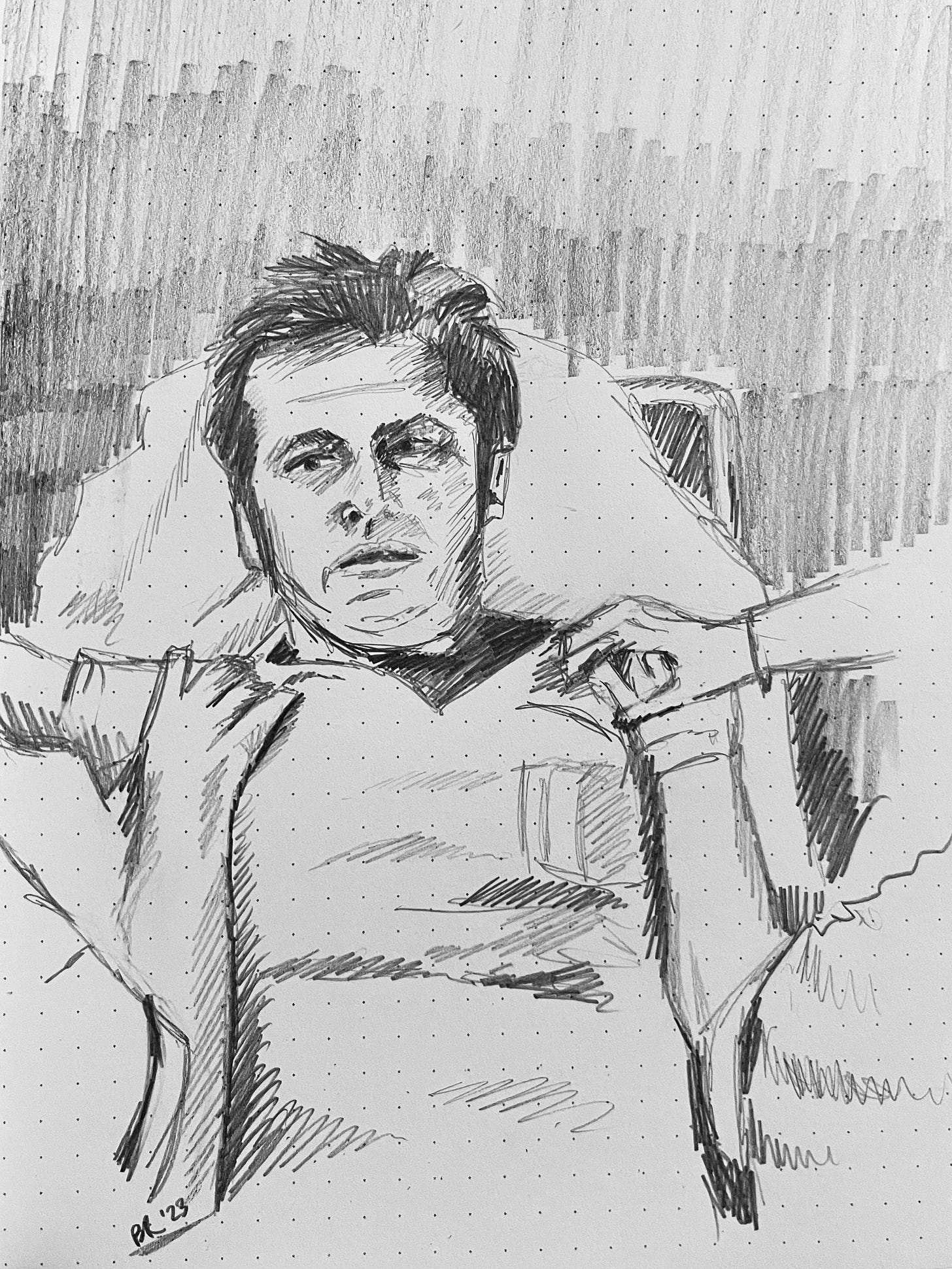

In my periphery, a husk in sterile green pajamas and burgundy robe appears in a doorway and begins to shuffle past me.

He doesn’t look at me, but past me. Through me. I’m trying to not look anywhere in particular - not even ahead to the room at the end of the hall that is my destination.

But it’s a long hallway and I’m full of anxiety and adrenaline, so my 15-year-old brain compels me to look around and ground myself. The walls are bare of any artwork to soothe the soul, only punctuated by a series of sterile metal doors lining one side of the corridor. Each of them is painted a dated, soothing pastel shade and adorned with a small sign. My curiosity gets the better of me, and so I can’t help myself but read them.

I don’t remember much, but I remember one of those door’s signs catching my breath and grounding this hospital visit in cold reality. It was only three letters long, but it said so much.

Mental illness has long been horror fodder, playing on fears of individual loss of control - loss of the very thing that makes us human and unique - and having that control taken from us without consent, either by fortune or by a beefy orderly. Aside from excellent performances and direction, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest frightens because it plays on these themes: when the patients cannot leave the tight, forcibly placid world of Nurse Ratched to express themselves, when it manhandles patients that misbehave - such as Randle McMurphy - onto gurneys for a light afternoon of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

The images are engrained: the teeth would clench, the mouth would spit and froth, the eyes would widen - all as a painful, punitive voltage coursed through the minds of the unwilling.

It never started as punitive, of course; institutional creativity came later. It started with the observation that people with high fevers often would have seizures as a result, and that those people who also had psychiatric conditions - schizophrenia or “paralytic dementia” (the psychosis one gets after syphilis enters the brain and chews the wires) - suddenly were relieved of their delusions and other demons. Julius Wagner-Jauregg tested the theory by treating those suffering from paralytic dementia with blood infected by malaria, finding the resulting fever and seizures would alleviate or cure the patient of their psychosis. This work - discovering the first biological treatment for a psychiatric condition - garnered the 1927 Nobel Prize.

But what if you’re fresh out of malaria?

Well, what about a drug to induce seizure instead? Ladislas Meduna used camphor to reset the psychotic brain. (Nowadays, we restrict our camphor use to anti-itch products and Vicks Vapo-Rub for chesty colds.) Others tried large quantities of insulin. Regardless of the poison of choice, though, seizure by drug for therapeutic effect was unpredictable1 and came with a high risk of irreversible brain damage, such as memory loss.2 This problem compelled Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini to investigate another cause of seizures more closely: electrical impulses.

Cerletti, whose laboratory research involved an examination of the [cellular] changes in…dogs’ brains following electrically induced seizures, postulated that electricity could be substituted for Metrozol as the convulsive stimulus for the treatment of psychosis.3

The machine they ultimately designed - via testing on a man with schizophrenia who was brought to the hospital a few weeks earlier by police - appeared to be a success.

I often refer to ECT as the ‘triple bypass of mental health.’ After cardiac surgery, patients must pay attention to exercise and eating habits to stay well. If ECT patients return to an emotional life of burgers and fries after successful ECT, odds of relapse increase. (Hersh, 2013)

ECT has had no shortage of controversy. We know the electrical impulses are doing something, but what in particular continues to be a question for clinical research. The debate was also partially due to sparse clinical guidelines that omitted the use of muscle relaxants or anesthetics, as well as the “…negative representation of ECT in films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Changeling and theatrical productions such as Next to Normal…even the recent Stephen King novel 11/22/63 features a murderous psychiatric patient who, of course, has just had a course of ECT…”4

Indeed, how deeply ingrained it is, that image of Jack Nicholson being wrested to the bed to be shocked into compliance. How entrenched that resulting fear; certainly it was for me, who, at 15, had seen the movie only a year or so prior to visiting the psychiatric ward and seeing that door.

Were people behind that non-descript door at that moment, getting ready to flip the switch on a hapless patient? Was it an abandoned closet that maintenance simply forgot to defrock and remove the placard?

Neither, it turns out. Over time and use of ECT, though, what practitioners learned is that it was actually an effective treatment for severe mood disorder; particularly, depression that hasn’t responded to other lines of treatment such as medications and psychotherapy.5 Practitioners also learned how to make the treatment humane: muscle relaxants, anesthesia, and much smaller currents to stimulate short, controlled seizure of 20-90 seconds.6

How it works, though, is still a mystery and under investigation. (I’ve read broad statements about brain plasticity - that the electrical impulses encourage new cell growth in areas of the brain that are impacted by anti-depressants.) It does still pose some risk of memory loss. However, unlike McMurphy and other patients, that risk is clearly communicated to patients before they lay down on the gurney.

Indeed, knowledge - be it informed consent for a potential patient, or research into clinical practices by a young visitor to a psychiatric hospital - is a powerful weapon to defend against the horror that lay in the unknown.

Other Reads

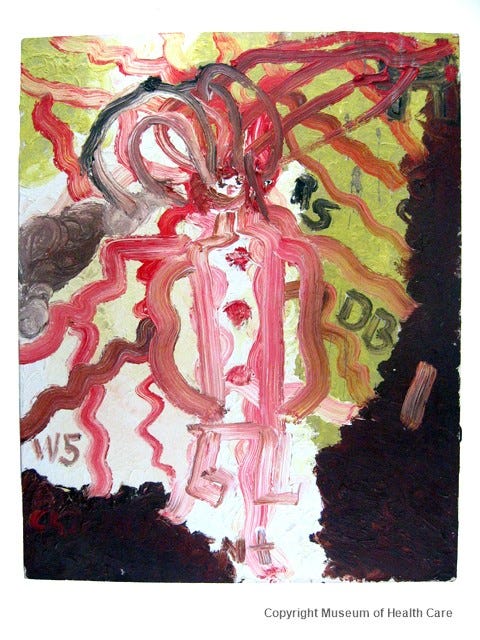

Knapp F. (2018). The Asylum That Gave Lou Reed Electroshock Therapy Is Also an Unforgettable Art Museum.

Wright J. (2016). What It’s Like Inside an Eerie Children’s Psychiatric Hospital Turned Opportunity Centre.

Thanks for reading today’s post, the second in my Spooky Science 2023 series. If you’re interested in reading more science-related content, please consider subscribing to receive weekly posts in your email or Substack app.

As well, check out The Sample. They curate articles from other blogs and newsletters, and send ones that match your interests.

Gazdag G, Ungvari GS. (2019). Electroconvulsive therapy: 80 years old and still going strong. World journal of psychiatry, 9(1), 1–6.

Aruta A. (2011). Shocking waves at the museum: the Bini-Cerletti electro-shock apparatus. Medical history, 55(3), 407–412.

Wright BA. (1990) An historical review of electroconvulsive therapy. Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry, 8(2), Article 10.

Hersh JK, Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) from the patient's perspective.Journal of Medical Ethics 2013;39:171-172.

American Psychiatric Association. What is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)?

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Electroconvulsive therapy.

Yeah that’s a great analogy! And I can understand why some people get that short term boost. That many neurons firing at once is like someone wiped your hard drive for 45 minutes. But I would love to see more research on how it works to unseat mental illnesses that are often so treatment resistant and deeply wired in the brain. What we know is promising ; what we could know with more research is exciting 🤩

Oh, gosh, no! When I was 18 I might have found the topic a bit triggering but now it’s just something I think I have a really interesting perspective on. And it’s not talked about a lot and I just think it’s honestly fascinating how humans can engineer what one person is born with to be therapy for another. It’s a testament to human ingenuity and how different every brain is- which is one reason I love neuroscience.

I hope more research about why it works *does* come out because that’s where I kind of get lost. I can understand why it would act as a short term reset but long term results ? I’d love to know