World of Wonder (Redux; #112)

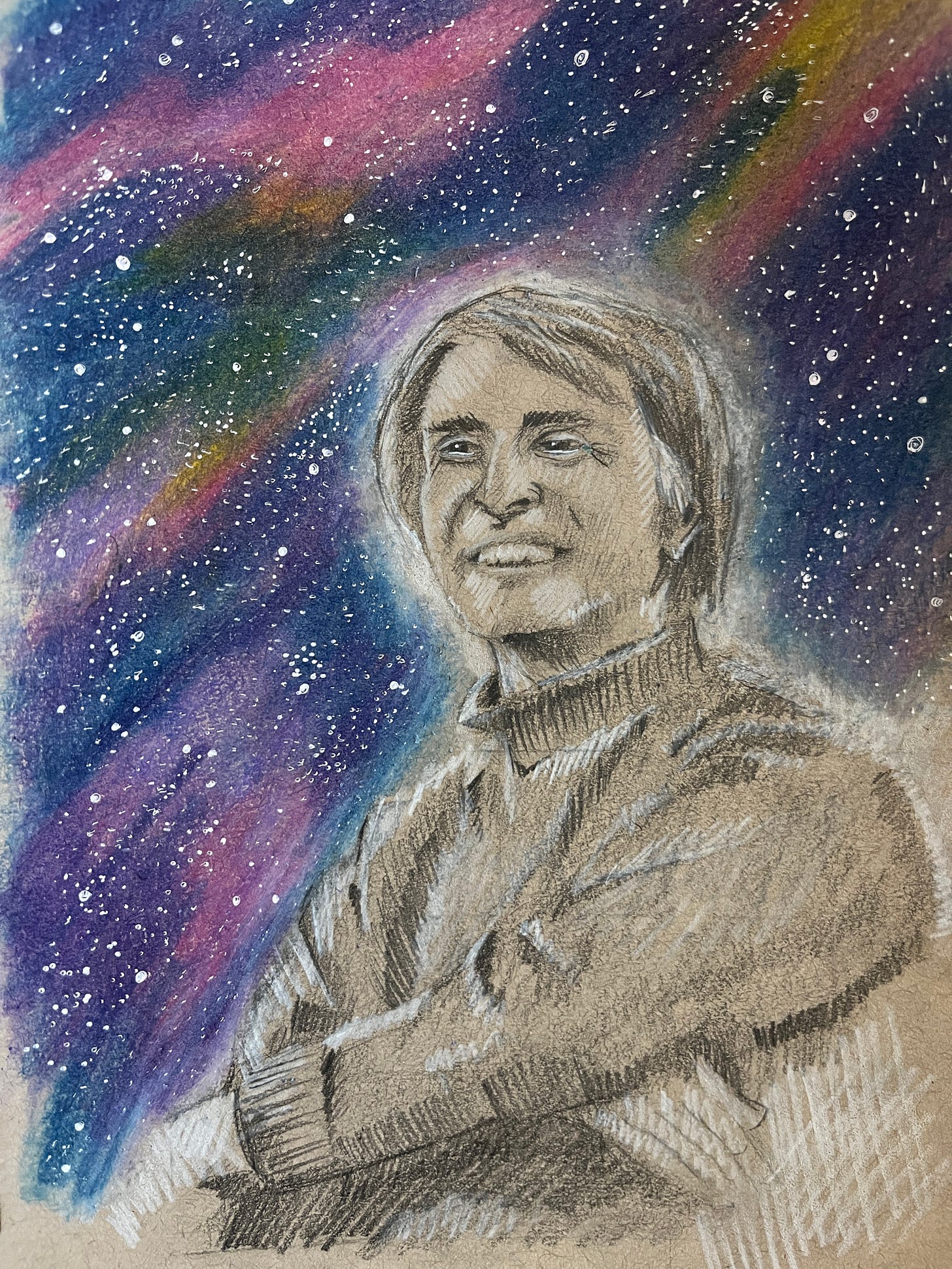

In which the author re-shares some Carl Sagan facts, and a few things learned about writing stories.

Originally published on August 4, 2022 as post #18, “World of Wonder” was Part 3 of an impromptu “Storytelling in Science” series I did when the Campfire was just starting to burn. While it can be read as a stand-alone post, you can also dive into Part 1 (#16, or, the case for using stories to share your science) and Part 2 (#17, or, choosing clearer, “plain” language to create our stories).

When my grade nine science teacher wanted us to understand the vastness of the universe, he wheeled out an aged TV on a cart1.

An experienced instructor, and as funny as he was, he knew that his bullet point notes on a chalkboard2 was a complete snooze to the feral pack of disinterested teens with glazed expressions before him. Instead, he left us in the capable hands of a true master of scientific storytelling.

When Dr. Carl Sagan, professor of astronomy at Cornell University, spoke in the language of science to other scientists, he did use the dispassionate prose of the academy.3 This unbiased, third-person perspective on science has a specific purpose: to offer an accounting of the work done without bias and emotion, so that it can stand in the harsh light of day and allow others to determine the quality of the work. And as a critical part of the science life cycle, writing “just the facts” - what we know, what we did for our experiment, and what we found - is trained into all researchers.

The problem with writing about science this way, though, is that it is based on the assumption that everyone - other researchers, funders, policymakers, the general public - learns by the brute force of technical words and jargon. That is, if we force-feed people the evidence from studies for long enough, they will simply be convinced that what is presented is important and worth considering.

Simply sharing evidence is not enough most times to convince your audience - and after that much time, money, and effort into doing the research, it’s a damn shame if it doesn’t resonate with a wider audience.

But the man who became the face of science for hundreds of millions around the world knew that how he shared science mattered, and that storytelling had a place in science for the right audience.

It was by chance that I picked up a book on storytelling in 2021. I should be ashamed to admit: I am very random in my book selections. It depends on current mood, what I just read, the cover. Yes, I absolutely will be drawn into borrowing or buying a book based on the graphic design of the cover.

All that to say, when it came to George Saunders’ book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, I don’t recall why I picked it up, or even thinking consciously that I wanted to begin more actively improving my writing. It was available at the library, and I wanted to read something different.

Saunders intersperses a selection of Russian short stories with his own marvelous insights on the way each master author used words to paint a scene.4 It’s a great read for both the stories and the education after each tale, but three lessons in particular have resonated with me as I explore storytelling in science (and improving my writing overall):

“It’s a Story, Not a Webcam.” Think about why you need to introduce a particular person into this story. Does it matter that the scientist had a teacher in grade nine that shared his love of Carl Sagan? For the purposes of your writing, and the idea that you want to share with the reader, will this information “alter, complicate, or deepen things”? If it doesn’t, then get rid of it.

Always Be Escalating. The words are important if they move the reader through the story. Using a science analogy, think of a story as “…a system for the transfer of energy. Energy, hopefully, gets made in the early pages and the trick, in the later pages, is to use that energy.” You need to write in a way that makes it clear to the reader that X was important for Y to happen.

Be Ruthlessly Efficient. Ask yourself if the words chosen or paragraphs written then use this potential energy to move the story along in a meaningful way. This is where the short stories provide great examples of economy of language with rich description of a person, scene, or idea. There was a purpose to the words used by the authors profiled in Saunders’ book.

The points above may seem especially daunting to those in the sciences without storytelling experience, but we forget that we already know how to do this work. In longer works like dissertations, the requirement is that you demonstrate an expansive knowledge and understanding of an area. When you then go to prepare a talk or an article based on this work, you never include all that information. Instead, you pick and choose what’s important to move the reader along. The same principle applies here: using your expansive knowledge and experiences, and then handpicking only those that move the story through the key actions.

I’ve started incorporating Saunders’ guidance into my process for all my writing; I begin first by writing with abandon. Once all the ideas are on paper or screen, then I’ll get ruthless and edit out what doesn’t serve the narrative, asking myself:

How does including this piece of information add to the story I’m building?

Does it cause something else to happen?

What’s the purpose of this character or another?

Have I reverted back to webcam mode and not story mode?

Do I need more coffee?5

For many who pursue science education beyond the early classrooms, we are forced to give up stories and wonder in favour of sharing science in tightly-written sentences on the narrow lines of black and blue lab books. Somehow, this is a demonstration of our validity as scientists - a criticism that even Dr. Sagan could not escape. While science generally holds him up in reverence for his storytelling talents, it wasn’t always the case during his lifetime. He was denied tenure track at Harvard (?!), and was refused a nomination to the National Academy of Sciences, on the grounds of not being a serious enough scientist.

While I cannot evaluate the strength of his astronomy work, I would argue that he was so serious as a scientist that he recognized the need to make it not just more accessible, but also more appreciated - by showing us just how wonderful a world it is.

And right there, I have placed myself within a sliver of beautiful, grungy time.

The OG smartboard.

For example, this paper on the evolution of surface temperatures and atmospheres on Earth and Mars.

Plus, the stories were a great way of introducing me to a group of authors I would otherwise not have experienced.

Always.

Very much enjoyed this article, Bryn! Thank you

Thank you for restacking! :)