Skyfall (#104)

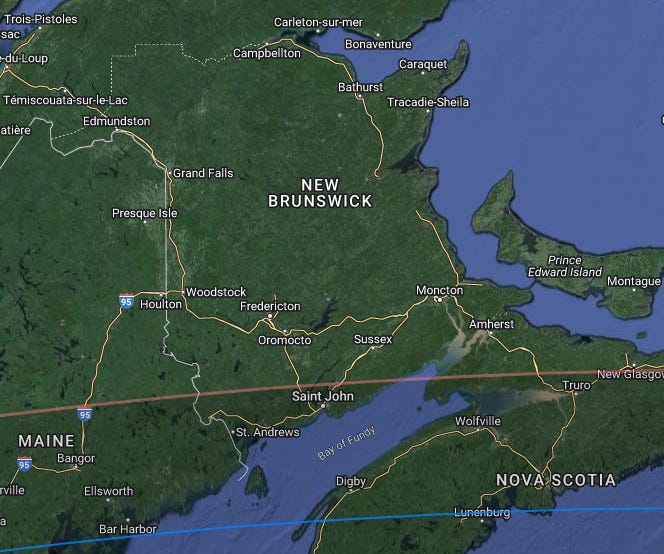

We flew our hatchback up to Fredericton, to see the total eclipse of the sun. Plus: Local astrophotography results and balloon telescopes!

It is 3:23 pm. The sun is basking in its’ own glow; the moon begins to creep onto centre stage to put on a show. First contact.

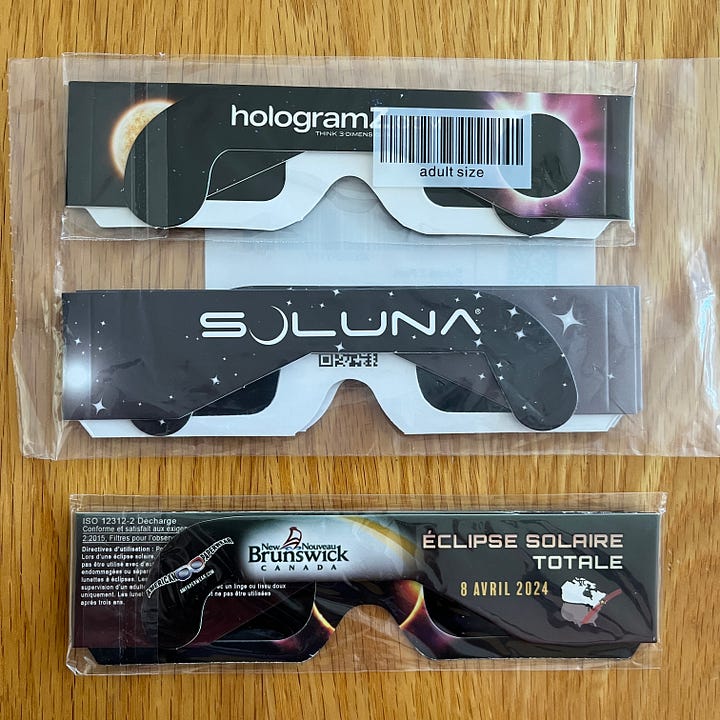

I don’t remember much about the solar eclipse I saw as a 12-year-old, standing in the parking lot of our middle school with my classmates, other than it happened. Cardboard viewers snugly set on our faces, we peered at the sky above as the sun disappeared from existence. An annular solar eclipse, the moon was at the farthest point in its orbit around the earth, and thus unable to fully obscure the sun.

It was pretty cool - Ben and I each have this memory of seeing it during our school days - but we don’t remember the world around us being that much different on that May afternoon12. So once we knew there was favourable weather for the total solar eclipse - the first for our region in over one thousand years - we firmed up plans to be in the path of totality.

And now that I’ve seen the total solar eclipse, I’m so glad we went for the full experience3. It was literally the difference between day and night.

Over the course of the 35 to 40 minutes, we stand in the diminishing sun but feel little effect of the waning light. The odd bird sings but much in the ma as it did before the partial eclipse started. The spring breeze continues to brush past our figures in the yard, but not so much that we need longer sleeves.

Then, a change. We seem to have hit a celestial tipping point, as the moon maintains the slow crawl over the sun’s face, but has now covered enough light that the yellowing world feels more like dusk. Unlike a summer evening, though, the air has changed. The breeze is no longer balmy but chilling, like you just opened the door of a refrigerator and are bathing in the cool air. The premise and the sudden ensuring panic of so many late-90s climate apocalypse movies becomes crystal clear; how dependent we are on the sun for life on this planet. How catastrophic its’ sudden absence would be.

It is 4:33 pm. The sun is nearly erased from our sight; the moon’s shadow nearly blankets us in the dark of night. Second contact.

The totality approaches, and soon the sky is only just light enough; the sliver of sun that remains still generating the light of a 1000 full moons on a clear night. Our discussion becomes more excited, as we peer at the sky to see the moon inch the final distance to totality.

Suddenly, a mourning dove cries behind us, appearing from the ether to frantically circle the fir trees. The poor thing thinks it has been caught out of its’ bedtime nest, and needs to quickly tuck in before monsters come out from under the bed and the depths of the brush.

It is 4:33 pm. The sun is no longer a star in our skies, the moon providing the star with an immersive disguise. Totality.

And then, it was night.

In our location, the path of totality allows us two minutes and 17 seconds of glasses-free viewing.

Other than the couple quick snaps of our dark surroundings, I just soaked it in: the cool air, the eerie calm supplanted by cheers and fanfare, the strange light of dusk during daytime.

I look up to the sky, and it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before: the shimmering corona as a sparkling thin ring of the highest-quality cut diamonds. At about the 7-o’clock position, a red bead of refraction appears - Baily’s Beads4, an effect that emerges from the sun peeking through a lunar valley.

“It kinda makes me want to cry”, one of our viewing party quietly remarks.

I felt the same way. There’s something quite simple yet profound about the concept of a singular event that you will only experience once and which thrusts the full scope of our being front and centre. How dependent we are on a bright ball of gas over which we have no control. How small we are in the grand scheme of a galaxy that carries on without any concern for our inconveniences. How large time is, knowing that neither I or anyone else around me watching this phenomenon will be around to see the next one in this region.

Holding infinity in the palm of your hand - or in the blink of an eye - is beautifully bittersweet.

It is 4:36 pm. The sun reasserts itself into the conversation, as the moon continues its nonchalant migration. Third contact.

And then, it’s over. The light begins to return to the backyard. Everyone is wearing big smiles, remarking on their favourite aspects of the event. By the time we pack up to drive the hour-plus home, the skies are bright and blue once again.

But us? No, I don’t think any of us will ever be the same.

This Week in SciArt

Stages of Contact

While I declined to prepare a proper astrophotography set-up with the DSLR, I did take a series of iPhone photos over the hour of first and second contact, totality, and third contact. The contrast is striking.

Stunning Sky Captures

Instead, I humbly turn over the reins to local photographers who I admire and who, quite simply, crushed the opportunity out of the park.

Brad Perry: “When the next total solar eclipse passes over Fredericton in 2079 and our son is 60 years old, I hope he looks back at this photo and remembers this day.” Excuse me while I deal with the dust in my eye. (Check out his website.)

Mark Hemmings: “The eclipse was far more incredible an experience than I assumed.” And this landscape of the eclipse at totality is far more incredible than anything I could conjure. (Check out his website.)

Balloon Bonus

Three years in the making, the citizen-led Solar Eclipse Balloon project found a quiet spot in the breezy spring day to launch a payload of six cameras into the sky.

David [Hunter] came up with the idea and brought together a team which has made this project possible. All have worked very hard to bring it to fruition and they are excited to demonstrate the results to all who will be in Florenceville-Bristol on the day of the total solar eclipse. (Background and Script to Supplement the Live Stream Footage of the Balloon Solar Eclipse Project)

After reaching a height of 66,000ft, the increasing pressure of the helium pushing outward from the balloon became more than the thinning atmospheric pressure on the balloon. It burst and returned the payload back the Earth. And because I am still a flight nerd, even twenty years after working for an airline, I had to check out the proceedings on my phone flight tracker.

Other References

Jubier X. (n.d.) Solar eclipses - Interactive Google maps.

Lea R. (2024, 7 April). The 5 stages of the 2024 total solar eclipse explained for April 8.

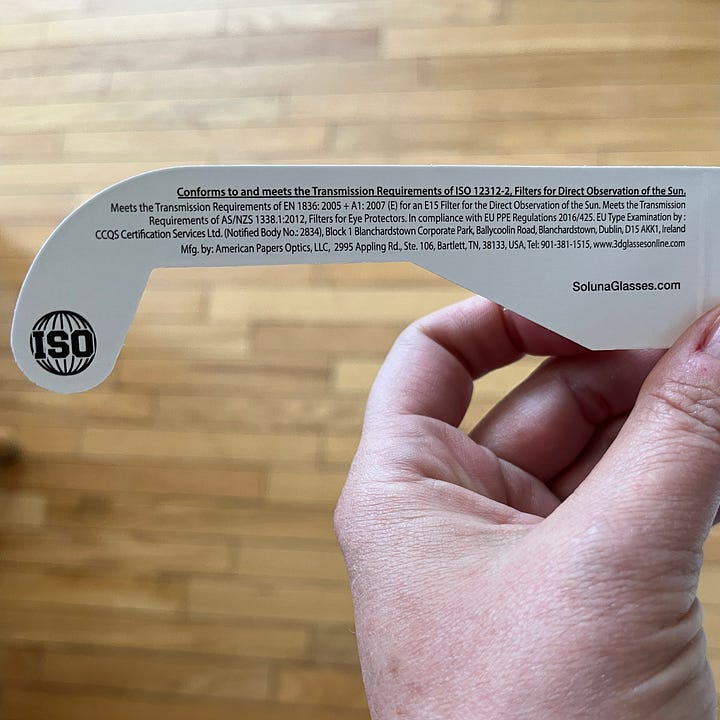

Middlekamp B. (2024, 25 March). Medical Neuroscience Graduate Organization educating about ocular health for April 8 solar eclipse. (Of note: “When there isn’t much light around us — which will occur during the eclipse — the pupil expands to allow in more light…When the pupil expands to accommodate for low light, the UV radiation can cause irreversible damage to cells in the eye.”)

Wikipedia. Solar eclipse of May 10, 1994.

Jubier X. (n.d.) Solar eclipses - Interactive Google maps.

Staying home would have meant only 98% coverage - still better but not the complete experience.

NASA. (2017, 5 October). Baily’s beads.

Thinking about it still makes me want to cry. It was incredible.

Wonderful Bryn! Thanks for sharing your wonderful writing and thoughts--what a day this was!